The Fermi Paradox truly is an issue!

This was written by Tim Urban 21 May 2014, from here

(along with plenty more good stuff) ==>

And here we have a Jan 2016 update ==>

and, equally amazing, we have this ==>

It turns out that roughly 68% of the universe is dark energy.

Dark matter makes up about 27%. The rest - everything on Earth,

everything ever observed with all of our instruments, all normal

matter - adds up to less than 5% of the universe.

See more at ==>

Everyone feels something when

they’re in a really good starry place on a really good

starry night and they look up and see this stunning picture

(right)

Some people stick with the traditional, feeling

struck by the epic beauty or blown away by the insane scale

of the universe. Personally, I go for the old “existential

meltdown followed by acting weird for the next half hour.”

But everyone feels something.

|

|

Physicist Enrico Fermi felt something too - ”Where is

everybody?”

|

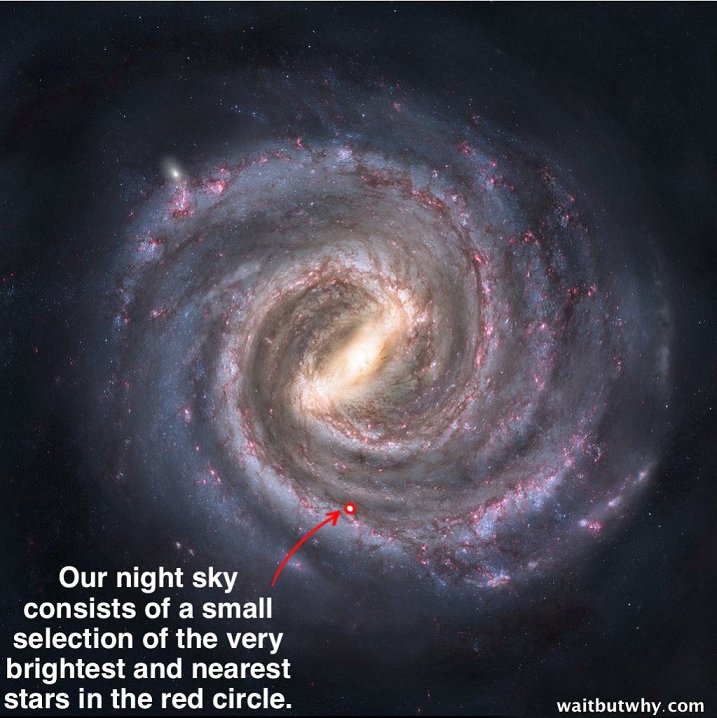

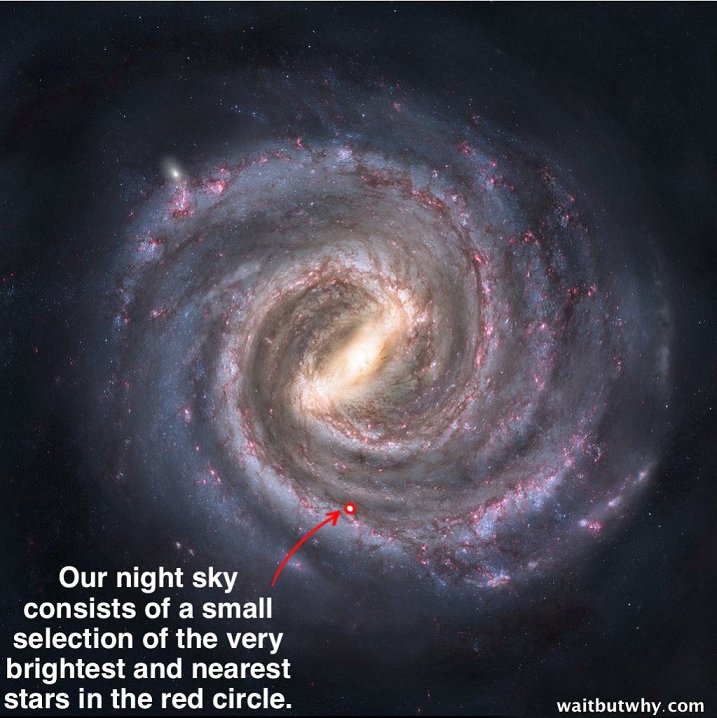

A really starry sky seems vast—but all we’re looking at is

our very local neighborhood. On the very best nights, we can

see up to about 2,500 stars (roughly one hundred-millionth

of the stars in our galaxy), and almost all of them are less

than 1,000 light years away from us (or 1% of the diameter

of the Milky Way). So what we’re really looking at is this

(left image)

|

When confronted with the topic of stars and galaxies, a question

that tantalizes most humans is, “Is there other intelligent life out

there?” Let’s put some numbers to it -

As many stars as there are in our galaxy (100 – 400 billion),

there are roughly an equal number of galaxies in the observable

universe—so for every star in the colossal Milky Way, there’s a

whole galaxy out there. All together, that comes out to the

typically quoted range of between 1022 and 1024 total stars, which

means that for every grain of sand on Earth, there are 10,000 stars

out there.

The science world isn’t in total agreement about what percentage

of those stars are “sun-like” (similar in size, temperature, and

luminosity)—opinions typically range from 5% to 20%. Going with the

most conservative side of that (5%), and the lower end for the

number of total stars (1022), gives us 500 quintillion, or 500

billion billion sun-like stars.

There’s also a debate over what percentage of those sun-like stars

might be orbited by an Earth-like planet (one with similar

temperature conditions that could have liquid water and potentially

support life similar to that on Earth). Some say it’s as high as

50%, but let’s go with the more conservative 22% that came out of a

recent PNAS study. That suggests that there’s a

potentially-habitable Earth-like planet orbiting at least 1% of the

total stars in the universe—a total of 100 billion billion

Earth-like planets.

So there are (at least) 100 Earth-like

planets for every grain of sand in the world. Think about that next

time you’re on the beach.

Moving forward, we have no choice but to get completely

speculative. Let’s imagine that after billions of years in

existence, 1% of Earth-like planets develop life (if that’s true,

every grain of sand would represent one planet with life on it). And

imagine that on 1% of those planets, the life advances to an

intelligent level like it did here on Earth. That would mean there

were 10 quadrillion, or 10 million billion intelligent civilizations

in the observable universe.

Moving back to just our galaxy, and doing the same math on the

lowest estimate for stars in the Milky Way (100 billion), we’d

estimate that there are 1 billion Earth-like planets and 100,000

intelligent civilizations in our galaxy.[1]

SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) is an organization

dedicated to listening for signals from other intelligent life. If

we’re right that there are 100,000 or more intelligent civilizations

in our galaxy, and even a fraction of them are sending out radio

waves or laser beams or other modes of attempting to contact others,

shouldn’t SETI’s satellite array pick up all kinds of signals?

But it hasn’t. Not one. Ever.

So, ”Where is everybody?”

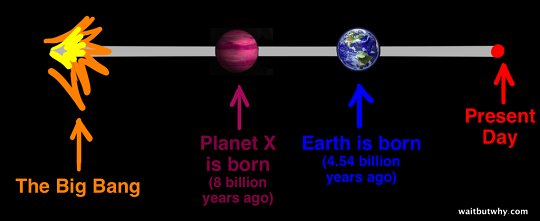

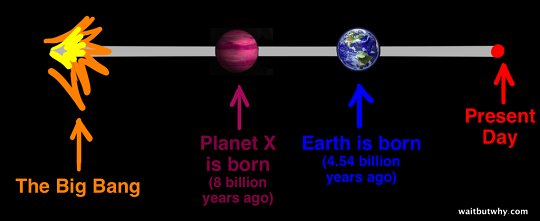

It gets stranger. Our sun is relatively young in

the lifespan of the universe. There are far older stars

with far older Earth-like planets, which should in theory

mean civilizations far more advanced than our own. As an

example, let’s compare our 4.54 billion-year-old Earth to

a hypothetical 8 billion-year-old Planet X.

|

|

|

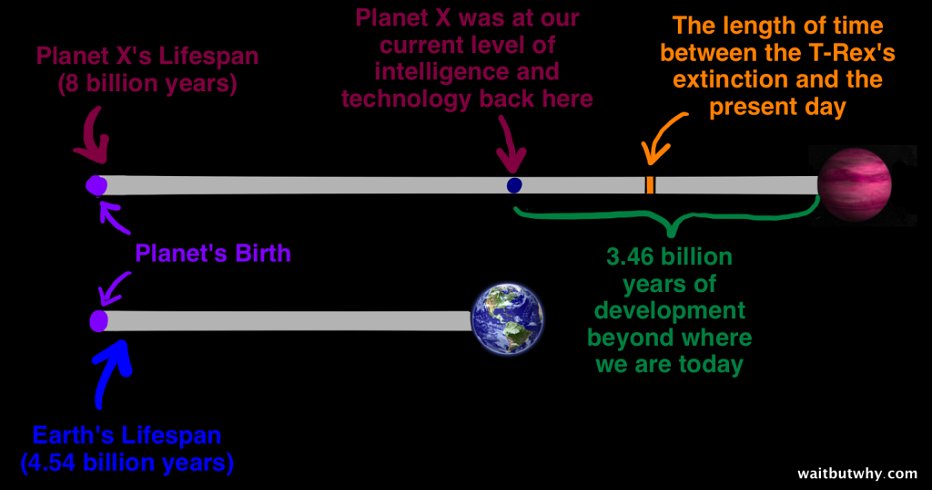

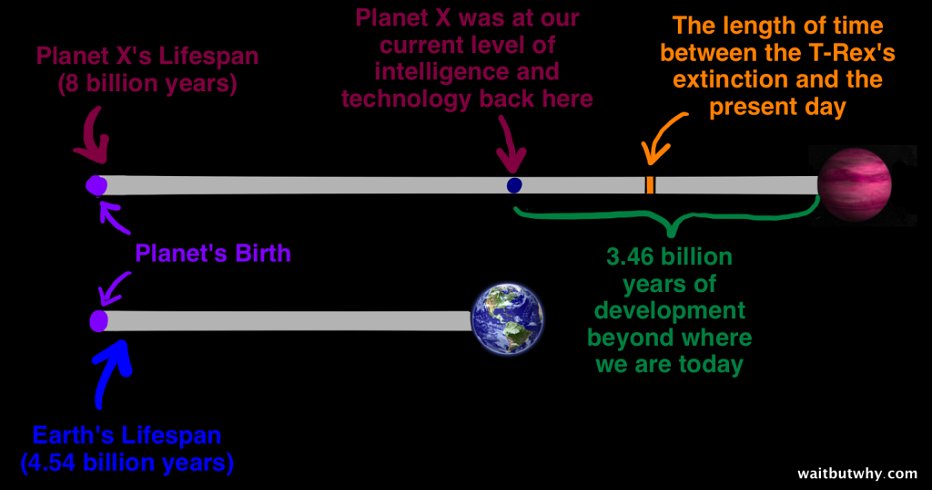

If Planet X has a similar story to Earth, let’s look at

where their civilization would be today, using the orange

time-span as a reference to show how huge the green

time-span is - (left image)

|

The technology and knowledge of a civilization

only 1,000 years ahead of us could be as shocking to us as

our world would be to a medieval person. A civilization 1

million years ahead of us might be as incomprehensible to

us as human culture is to chimpanzees. And Planet XDyson

Sphere is 3.4 billion years ahead of us…

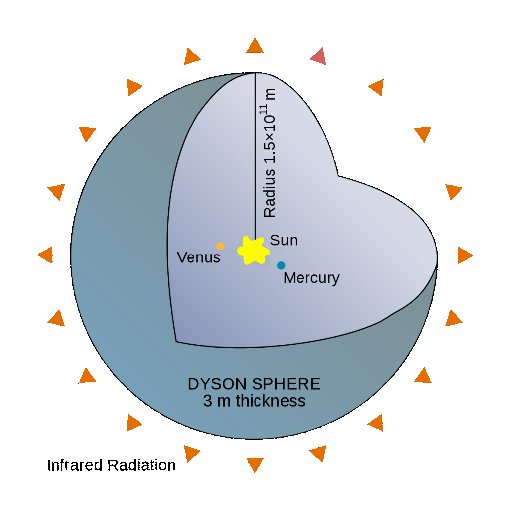

There’s something called The Kardashev Scale, which helps

us group intelligent civilizations into three broad

categories by the amount of energy they use:

A Type I Civilization has the ability to use all of the

energy from their sun that falls on their planet. We’re

not quite a Type I Civilization, but we’re close (Carl

Sagan created a formula for this scale which puts us at a

Type 0.7 Civilization).

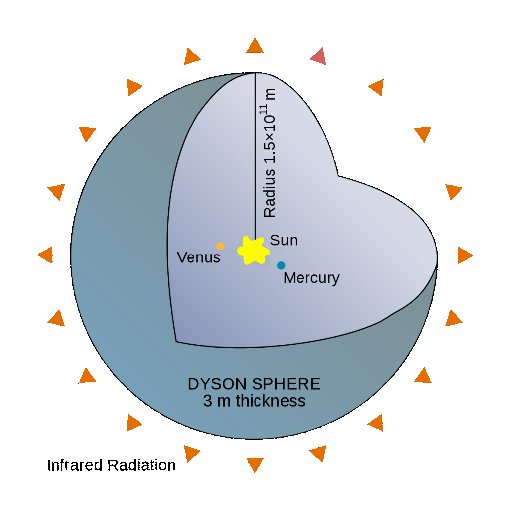

A Type II Civilization can harness all of the energy of

their host star. Our feeble Type I brains can hardly

imagine how someone would do this, but we’ve tried our

best, imagining things like a Dyson Sphere.

|

|

|

A Type III Civilization blows the other two away,

accessing power comparable to that emitted of all of the

suns of their galaxy, or for us, the entire Milky Way

galaxy.

If this level of advancement sounds hard to believe,

remember Planet X above and their 3.4 billion years of

further development. If a civilization on Planet X were

similar to ours and were able to survive all the way to

Type III level, the natural thought is that they’d

probably have mastered inter-stellar travel by now,

possibly even colonizing the entire galaxy.

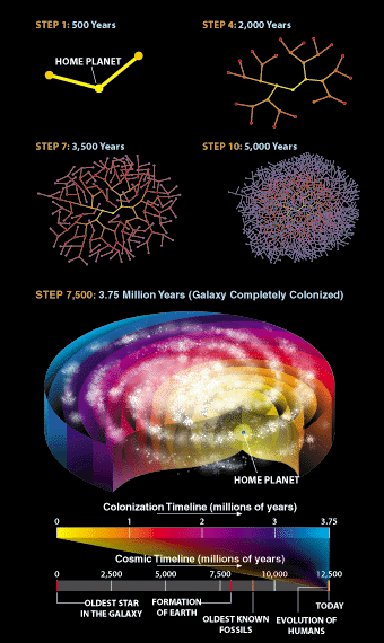

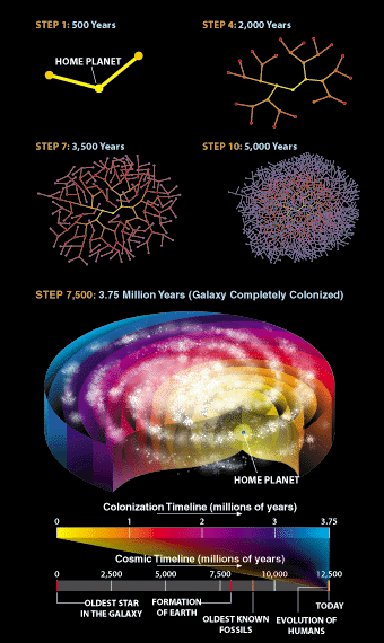

One hypothesis as to how galactic colonization could

happen is by creating machinery that can travel to other

planets, spend 500 years or so self-replicating using the

raw materials on their new planet, and then send two

replicas off to do the same thing. Even without traveling

anywhere near the speed of light, this process would

colonize the whole galaxy in 3.75 million years, a

relative blink of an eye when talking in the scale of

billions of years: (left image)

|

Continuing to speculate, if 1% of intelligent life

survives long enough to become a potentially

galaxy-colonizing Type III Civilization, our calculations

above suggest that there should be at least 1,000 Type III

Civilizations in our galaxy alone — and given the power of

such a civilization, their presence would likely be pretty

noticeable. And yet, we see nothing, hear nothing, and

we’re visited by no one.

So where is everybody?

We have no answer to the Fermi Paradox — the best we can

do is “possible explanations.” And if you ask ten

different scientists what their hunch is about the correct

one, you’ll get ten different answers. You know when you

hear about humans of the past debating whether the Earth

was round or if the sun revolved around the Earth or

thinking that lightning happened because of Zeus, and they

seem so primitive and in the dark? That’s about where we

are with this topic.

|

In taking a look at some of the most-discussed possible

explanations for the Fermi Paradox, let’s divide them into

two broad categories—those explanations which assume that

there’s no sign of Type II and Type III Civilizations

because there are none of them out there, and those which

assume they’re out there and we’re not seeing or hearing

anything for other reasons:

Explanation Group 1: There are no signs of higher (Type II

and III) civilizations because there are no higher

civilizations in existence.

Those who subscribe to Group 1 explanations point to

something called the non-exclusivity problem, which

rebuffs any theory that says, “There are higher

civilizations, but none of them have made any kind of

contact with us because they all _____.” Group 1 people

look at the math, which says there should be so many

thousands (or millions) of higher civilizations, that at

least one of them would be an exception to the rule. Even

if a theory held for 99.99% of higher civilizations, the

other .01% would behave differently and we’d become aware

of their existence.

Therefore, say Group 1 explanations, it must be that there

are no super-advanced civilizations. And since the math

suggests that there are thousands of them just in our own

galaxy, something else must be going on.

|

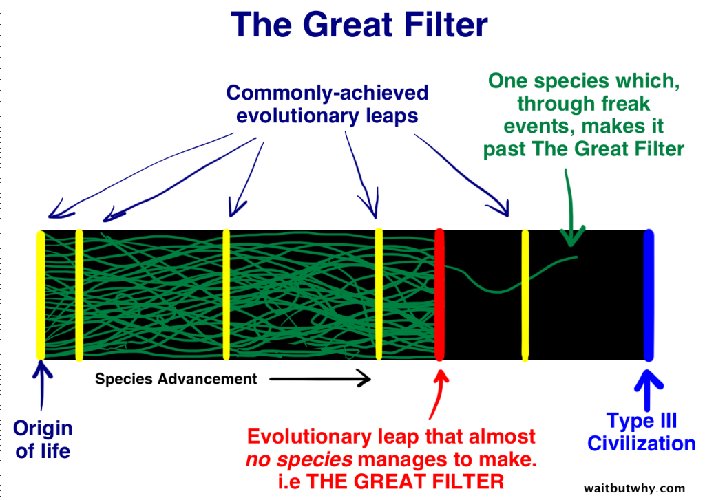

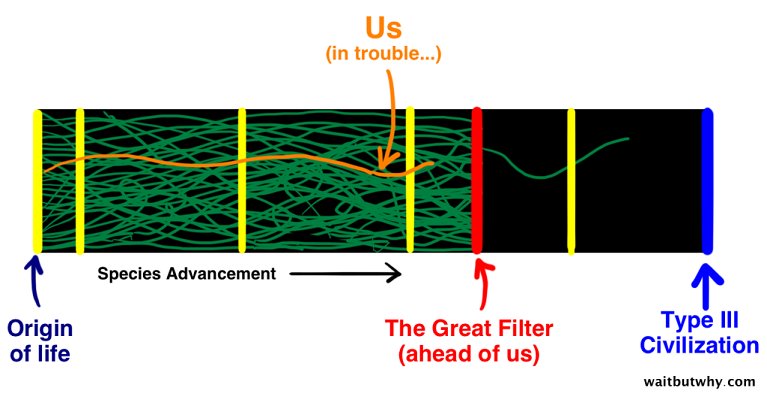

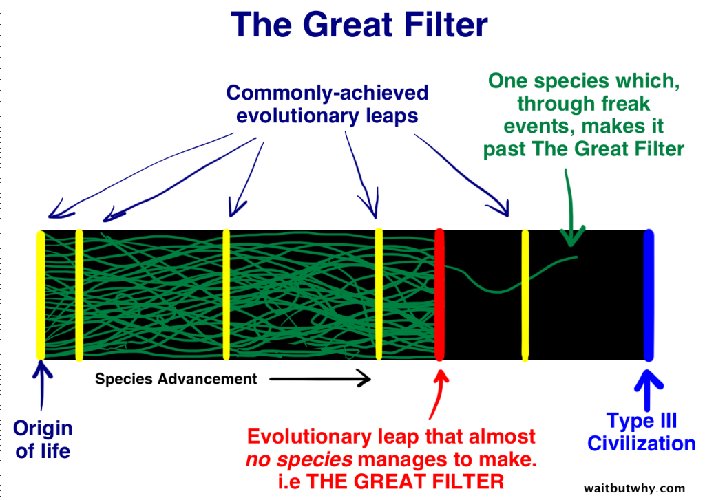

This something else is called The Great Filter.

The Great Filter theory says that at some point from pre-life to

Type III intelligence, there’s a wall that all or nearly all

attempts at life hit. There’s some stage in that long evolutionary

process that is extremely unlikely or impossible for life to get

beyond. That stage is The Great Filter.

If this theory is true, the big question is,

Where in the timeline does the Great Filter occur?

It turns out that when it comes to the fate of humankind,

this question is very important. Depending on where The

Great Filter occurs, we’re left with three possible

realities:

We’re rare, we’re first, or

we’re fucked.

|

|

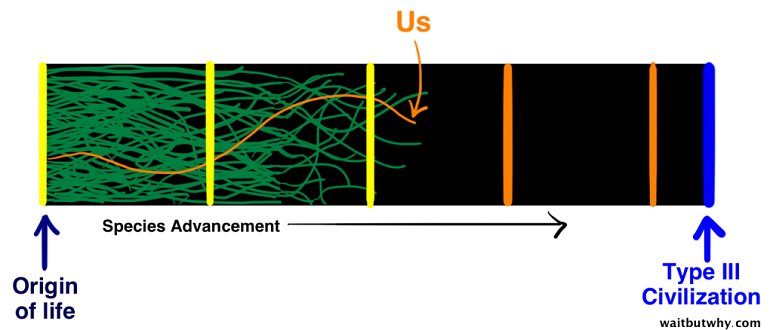

1. We’re Rare (The Great Filter is Behind Us)

One hope we have is that The Great Filter is behind us—we

managed to surpass it, which would mean it’s extremely rare for

life to make it to our level of intelligence. The diagram below

shows only two species making it past, and we’re one of them.

The GREAT FILTER is BEHIND

US

|

This scenario would explain why there are no Type III

Civilizations…but it would also mean that we could be one

of the few exceptions now that we’ve made it this far.

It would mean we have hope. On the surface, this sounds a

bit like people 500 years ago suggesting that the Earth is

the center of the universe - it implies that we’re

special.

However, something scientists call “observation selection

effect” suggests that anyone who is pondering their own

rarity is inherently part of an intelligent life “success

story” -

and whether they’re actually rare or quite common, the

thoughts they ponder and conclusions they draw will be

identical. This forces us to admit that being special is

at least a possibility.

|

And if we are special, when exactly

did we become special—i.e. which step did we surpass that almost

everyone else gets stuck on?

One possibility: The Great Filter could be at the very

beginning—it might be incredibly unusual for life to begin at all.

This is a candidate because it took about a billion years of

Earth’s existence to finally happen, and because we have tried

extensively to replicate that event in labs and have never been

able to do it. If this is indeed The Great Filter, it would mean

that not only is there no intelligent life out there, there may be

no other life at all.

Another possibility: The Great Filter could be the jump from the

simple prokaryote cell to the complex eukaryote cell. After

prokaryotes came into being, they remained that way for almost two

billion years before making the evolutionary jump to being complex

and having a nucleus. If this is The Great Filter, it would mean

the universe is teeming with simple prokaryote cells and almost

nothing beyond that.

There are a number of other possibilities—some even think the most

recent leap we’ve made to our current intelligence is a Great

Filter candidate. While the leap from semi-intelligent life

(chimps) to intelligent life (humans) doesn’t at first seem like a

miraculous step, Steven Pinker rejects the idea of an inevitable

“climb upward” of evolution: “Since evolution does not strive for

a goal but just happens, it uses the adaptation most useful for a

given ecological niche, and the fact that, on Earth, this led to

technological intelligence only once so far may suggest that this

outcome of natural selection is rare and hence by no means a

certain development of the evolution of a tree of life.”

Most leaps do not qualify as Great Filter candidates. Any possible

Great Filter must be one-in-a-billion type thing where one or more

total freak occurrences need to happen to provide a crazy

exception—for that reason, something like the jump from

single-cell to multi-cellular life is ruled out, because it has

occurred as many as 46 times, in isolated incidents, just on this

planet alone. For the same reason, if we were to find a fossilized

eukaryote cell on Mars, it would rule the above “simple-to-complex

cell” leap out as a possible Great Filter (as well as anything

before that point on the evolutionary chain)—because if it

happened on both Earth and Mars, it’s almost definitely not a

one-in-a-billion freak occurrence.

If we are indeed rare, it could be because of a fluky biological

event, but it also could be attributed to what is called the Rare

Earth Hypothesis, which suggests that though there may be many

Earth-like planets, the particular conditions on Earth—whether

related to the specifics of this solar system, its relationship

with the moon (a moon that large is unusual for such a small

planet and contributes to our particular weather and ocean

conditions), or something about the planet itself—are

exceptionally friendly to life.

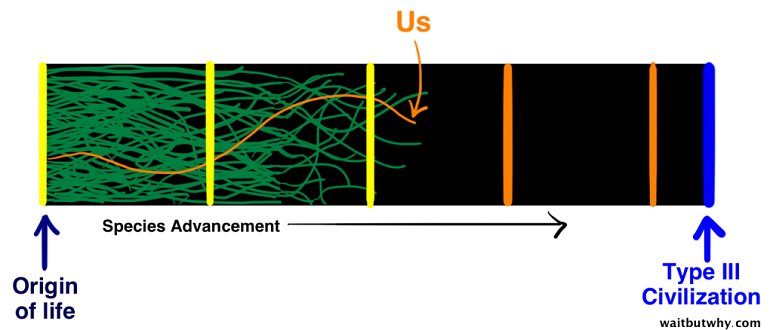

2. We’re the First - Are we the First?

For Group 1 Thinkers, if the Great Filter is not behind us, the

one hope we have is that conditions in the universe are just

recently, for the first time since the Big Bang, reaching a place

that would allow intelligent life to develop. In that case, we and

many other species may be on our way to super-intelligence, and it

simply hasn’t happened yet. We happen to be here at the right time

to become one of the first super-intelligent civilizations.

One example of a phenomenon that could make this

realistic is the prevalence of gamma-ray bursts, insanely

huge explosions that we’ve observed in distant galaxies.

In the same way that it took the early Earth a few hundred

million years before the asteroids and volcanoes died down

and life became possible, it could be that the first chunk

of the universe’s existence was full of cataclysmic events

like gamma-ray bursts that would incinerate everything

nearby from time to time and prevent any life from

developing past a certain stage. Now, perhaps, we’re in

the midst of an astrobiological phase transition and this

is the first time any life has been able to evolve for

this long, uninterrupted.

|

|

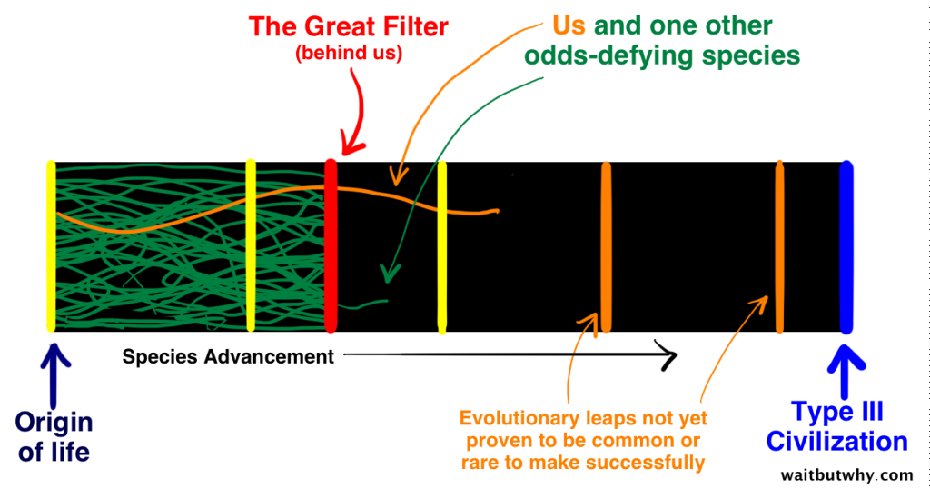

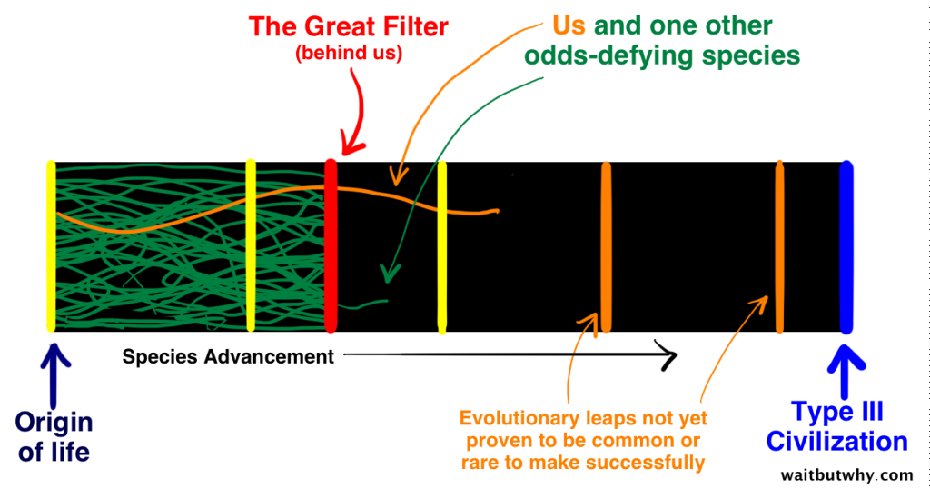

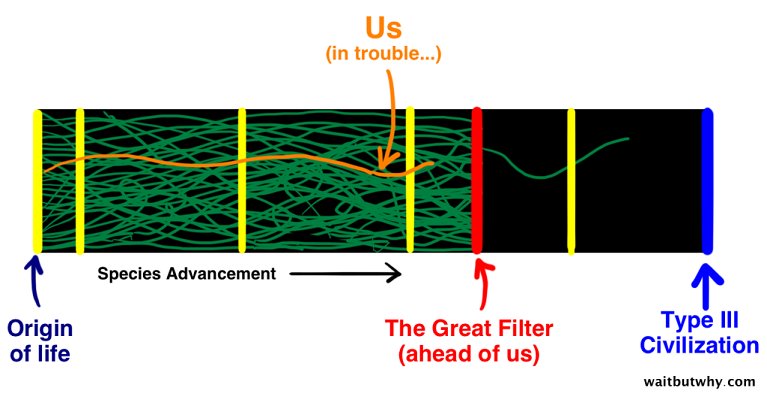

3. We’re Fucked (The Great Filter is Ahead of Us)

If we’re neither rare nor early, Group 1 thinkers conclude that

The Great Filter must be in our future. This would suggest that

life regularly evolves to where we are, but that something

prevents life from going much further and reaching high

intelligence in almost all cases—and we’re unlikely to be an

exception.

The GREAT FILTER is AHEAD

of US

|

One possible future is a regularly-occurring cataclysmic

natural event, like the above-mentioned gamma-ray bursts,

except they’re unfortunately not done yet and it’s just a

matter of time before all life on Earth is suddenly wiped

out by one. Another candidate is the possible

inevitability that nearly all intelligent civilizations

end up destroying themselves once a certain level of

technology is reached.

|

This is why Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom says that

“no news is good news.” The discovery of even simple life on Mars

would be devastating, because it would cut out a number of

potential Great Filters behind us. And if we were to find

fossilized complex life on Mars, Bostrom says “it would be by far

the worst news ever printed on a newspaper cover,” because it

would mean The Great Filter is almost definitely ahead of

us—ultimately dooming the species. Bostrom believes that when it

comes to The Fermi Paradox, “the silence of the night sky is

golden.”

Explanation Group 2: Type II and III

intelligent civilizations are out there—and there are logical

reasons why we might not have heard from them.

Group 2 explanations

get rid of any notion that we’re rare or special or the first at

anything—on the contrary, they believe in the Mediocrity

Principle, whose starting point is that there is nothing unusual

or rare about our galaxy, solar system, planet, or level of

intelligence, until evidence proves otherwise. They’re also much

less quick to assume that the lack of evidence of higher

intelligence beings is evidence of their nonexistence—emphasizing

the fact that our search for signals stretches only about 100

light years away from us (0.1% across the galaxy) and suggesting a

number of possible explanations. Here are 10:

Possibility 1)

Super-intelligent life could very well have already visited

Earth, but before we were here. In the scheme of things, sentient

humans have only been around for about 50,000 years, a little blip

of time. If contact happened before then, it might have made some

ducks flip out and run into the water and that’s it. Further,

recorded history only goes back 5,500 years—a group of ancient

hunter-gatherer tribes may have experienced some crazy alien shit,

but they had no good way to tell anyone in the future about it.

Possibility 2)

The galaxy has been colonized, but we just live in some desolate

rural area of the galaxy. The Americas may have been colonized by

Europeans long before anyone in a small Inuit tribe in far

northern Canada realized it had happened. There could be an

urbanization component to the interstellar dwellings of higher

species, in which all the neighboring solar systems in a certain

area are colonized and in communication, and it would be

impractical and purposeless for anyone to deal with coming all the

way out to the random part of the spiral where we live.

Possibility 3)

The entire concept of physical colonization is a hilariously

backward concept to a more advanced species. Remember the picture

of the Type II Civilization above with the sphere around their

star? With all that energy, they might have created a perfect

environment for themselves that satisfies their every need. They

might have crazy-advanced ways of reducing their need for

resources and zero interest in leaving their happy utopia to

explore the cold, empty, undeveloped universe.

An even more advanced civilization might view the entire physical

world as a horribly primitive place, having long ago conquered

their own biology and uploaded their brains to a virtual reality,

eternal-life paradise. Living in the physical world of biology,

mortality, wants, and needs might seem to them the way we view

primitive ocean species living in the frigid, dark sea. FYI,

thinking about another life form having bested mortality makes me

incredibly jealous and upset. We need more Afterlife research.

Possibility 4)

There are scary predator civilizations out there, and most

intelligent life knows better than to broadcast any outgoing

signals and advertise their location. This is an unpleasant

concept and would help explain the lack of any signals being

received by the SETI satellites. It also means that we might be

the super naive newbies who are being unbelievably stupid and

risky by ever broadcasting outward signals. There’s a debate going

on currently about whether we should engage in METI (Messaging to

Extraterrestrial Intelligence—the reverse of SETI) or not, and

most people say we should not. Stephen Hawking warns, “If aliens

visit us, the outcome would be much as when Columbus landed in

America, which didn’t turn out well for the Native Americans.”

Even Carl Sagan (a general believer that any civilization advanced

enough for interstellar travel would be altruistic, not hostile)

called the practice of METI “deeply unwise and immature,” and

recommended that “the newest children in a strange and uncertain

cosmos should listen quietly for a long time, patiently learning

about the universe and comparing notes, before shouting into an

unknown jungle that we do not understand.” Scary.[2]

Possibility 5)

There’s only one instance of higher-intelligent life—a

“superpredator” civilization (like humans are here on Earth)—who

is far more advanced than everyone else and keeps it that way by

exterminating any intelligent civilization once they get past a

certain level. This would suck. The way it might work is that it’s

an inefficient use of resources to exterminate all emerging

intelligences, maybe because most die out on their own. But past a

certain point, the super beings make their move—because to them,

an emerging intelligent species becomes like a virus as it starts

to grow and spread. This theory suggests that whoever was the

first in the galaxy to reach intelligence won, and now no one else

has a chance. This would explain the lack of activity out there

because it would keep the number of super-intelligent

civilizations to just one.

Possibility 6)

There’s plenty of activity and noise out there, but our

technology is too primitive and we’re listening for the wrong

things. Like walking into a modern-day office building, turning on

a walkie-talkie, and when you hear no activity (which of course

you wouldn’t hear because everyone’s texting, not using

walkie-talkies), determining that the building must be empty. Or

maybe, as Carl Sagan has pointed out, it could be that our minds

work exponentially faster or slower than another form of

intelligence out there—e.g. it takes them 12 years to say “Hello,”

and when we hear that communication, it just sounds like white

noise to us.

Possibility 7)

We are receiving contact from other intelligent life, but the

government is hiding it. This is an idiotic theory, but I had to

mention it because it’s talked about so much.

Possibility 8)

Higher civilizations are aware of us and observing us (AKA the

“Zoo Hypothesis”). As far as we know, super-intelligent

civilizations exist in a tightly-regulated galaxy, and our Earth

is treated like part of a vast and protected national park, with a

strict “Look but don’t touch” rule for planets like ours. We

wouldn’t notice them, because if a far smarter species wanted to

observe us, it would know how to easily do so without us realizing

it. Maybe there’s a rule similar to the Star Trek's Prime

Directive which prohibits super-intelligent beings from making any

open contact with lesser species like us or revealing themselves

in any way, until the lesser species has reached a certain level

of intelligence.

Possibility 9)

Higher civilizations are here, all around us. But we’re too

primitive to perceive them. Michio Kaku sums it up like this:

Let's say we have an ant hill in the middle of the forest. And

right next to the ant hill, they’re building a ten-lane

super-highway. And the question is “Would the ants be able to

understand what a ten-lane super-highway is? Would the ants be

able to understand the technology and the intentions of the beings

building the highway next to them?

So it’s not that we can’t pick up

the signals from Planet X using our technology, it’s that we can’t

even comprehend what the beings from Planet X are or what they’re

trying to do. It’s so beyond us that even if they really wanted to

enlighten us, it would be like trying to teach ants about the

internet.

Along those lines, this may also be an answer to “Well if there

are so many fancy Type III Civilizations, why haven’t they

contacted us yet?” To answer that, let’s ask ourselves—when

Pizarro made his way into Peru, did he stop for a while at an

anthill to try to communicate? Was he magnanimous, trying to help

the ants in the anthill? Did he become hostile and slow his

original mission down in order to smash the anthill apart? Or was

the anthill of complete and utter and eternal irrelevance to

Pizarro? That might be our situation here.

Possibility 10)

We’re completely wrong about our reality. There are a lot of

ways we could just be totally off with everything we think. The

universe might appear one way and be something else entirely, like

a hologram. Or maybe we’re the aliens and we were planted here as

an experiment or as a form of fertilizer. There’s even a chance

that we’re all part of a computer simulation by some researcher

from another world, and other forms of life simply weren’t

programmed into the simulation.

As we continue along with our possibly-futile search for

extraterrestrial intelligence, I’m not really sure what I’m

rooting for. Frankly, learning either that we’re officially alone

in the universe or that we’re officially joined by others would be

creepy, which is a theme with all of the surreal story-lines

listed above—whatever the truth actually is, it’s mind-blowing.

Beyond its shocking science fiction component, The Fermi Paradox

also leaves me with a deep humbling. Not just the normal “Oh yeah,

I’m microscopic and my existence lasts for three seconds” humbling

that the universe always triggers. The Fermi Paradox brings out a

sharper, more personal humbling, one that can only happen after

spending hours of research hearing your species’ most renowned

scientists present insane theories, change their minds again and

again, and wildly contradict each other — reminding us that future

generations will look at us the same way we see the ancient people

who were sure that the stars were the underside of the dome of

heaven, and they’ll think “Wow they really had no idea what was

going on.”

Compounding all of this is the blow to our species’ self-esteem

that comes with all of this talk about Type II and III

Civilizations. Here on Earth, we’re the king of our little castle,

proud ruler of the huge group of imbeciles who share the planet

with us. And in this bubble with no competition and no one to

judge us, it’s rare that we’re ever confronted with the concept of

being a dramatically inferior species to anyone. But after

spending a lot of time with Type II and III Civilizations over the

past week, our power and pride are seeming soft and self-deluding.

That said, given that my normal outlook is that humanity is a

lonely orphan on a tiny rock in the middle of a desolate universe,

the humbling fact that we’re probably not as smart as we think we

are, and the possibility that a lot of what we’re sure about might

be wrong, sounds wonderful. It opens the door just a crack that

maybe, just maybe, there might be more to the story than we

realize.

And here we have a Jan 2016 update ==>

(End of page body)